Models of Executive Functioning in ADHD

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often reduced to problems of attention or impulsivity. Clinically, however, what most adults and adolescents struggle with is something broader and more disabling: executive dysfunction—difficulty organizing behavior over time in the service of goals.

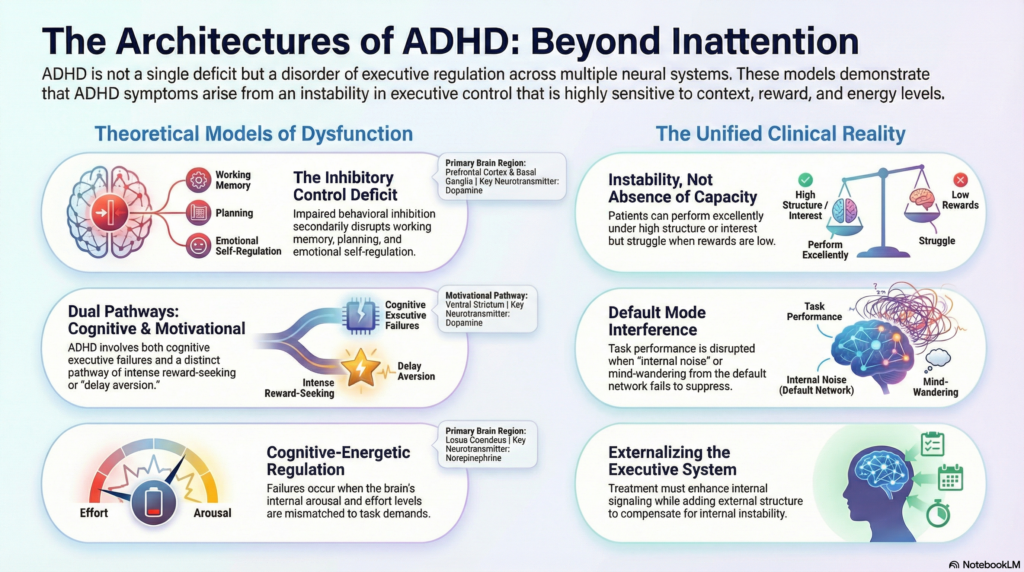

Over the past three decades, several theoretical models have attempted to explain why executive control fails in ADHD. Each model captures a different layer of the disorder, and together they reveal an important truth: ADHD is not a single executive deficit, but a disorder of executive regulation across multiple systems.

Over the past three decades, several theoretical models have attempted to explain why executive control fails in ADHD. Each model captures a different layer of the disorder, and together they reveal an important truth: ADHD is not a single executive deficit, but a disorder of executive regulation across multiple systems.

1. Barkley’s Inhibitory Control Model

ADHD as a disorder of behavioral inhibition

Russell Barkley’s model is one of the most influential and clinically intuitive frameworks.

Core idea

The primary deficit in ADHD is impaired behavioral inhibition, which secondarily disrupts other executive functions.

According to Barkley, inhibition failure leads to impairment in:

-

Working memory (especially non-verbal)

-

Internalization of speech

-

Self-regulation of affect and motivation

-

Reconstitution (planning and problem-solving)

Neurobiological grounding

-

Frontostriatal circuitry (PFC–basal ganglia)

-

Dopaminergic modulation of inhibitory control

-

Delayed maturation of prefrontal cortex

Clinical strength

Explains:

-

Impulsivity

-

Emotional dysregulation

-

“Knowing what to do but not doing it”

Limitation

Does not fully explain:

-

Pure inattentive presentations

-

Motivational variability

-

Delay aversion

2. Dual Pathway Model

ADHD as executive dysfunction and motivational dysregulation

Proposed by Sonuga-Barke, this model challenged the idea that ADHD is purely an executive disorder.

Core idea

There are two partially independent pathways to ADHD symptoms:

-

Executive dysfunction pathway

-

Deficits in inhibition, working memory, planning

-

-

Motivational pathway (delay aversion)

-

Strong preference for immediate rewards

-

Difficulty tolerating delay

-

Neurobiological grounding

-

Executive pathway: frontoparietal control network

-

Motivational pathway: ventral striatum, orbitofrontal cortex

Clinical strength

Explains:

-

Why some patients perform well under urgency

-

Why rewards dramatically change behavior

-

Variability across contexts

Limitation

Still treats executive functions as relatively unitary within the cognitive pathway.

3. Cognitive–Energetic Model

ADHD as impaired regulation of mental effort

Proposed by Sergeant, this model reframes executive dysfunction as a problem of state regulation, not capacity.

Core idea

ADHD reflects difficulty regulating:

-

Arousal

-

Activation

-

Effort

Executive failures occur when energetic state is mismatched to task demands.

Neurobiological grounding

-

Locus coeruleus–noradrenergic system

-

Dopamine–norepinephrine balance

-

Arousal networks interacting with PFC

Clinical strength

Explains:

-

Fluctuating performance

-

Fatigue with low-stimulation tasks

-

Improvement with novelty or challenge

Limitation

Less precise in mapping specific executive processes like planning or inhibition.

4. Executive Attention Network Model

ADHD as impaired top-down attentional control

This model emphasizes dysfunction in the executive attention system, particularly the ability to resolve conflict and maintain task goals.

Core idea

ADHD reflects weakness in the anterior cingulate–prefrontal network responsible for executive attention.

Neurobiological grounding

-

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)

-

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

-

Frontoparietal connectivity

Clinical strength

Explains:

-

Distractibility

-

Errors under cognitive load

-

Poor conflict monitoring

Limitation

Does not fully address emotional or motivational dysregulation.

5. Default Mode Interference Model

ADHD as failure to suppress internal noise

A more recent network-based perspective.

Core idea

In ADHD, the default mode network (DMN) intrudes during task performance due to inadequate suppression by executive networks.

Neurobiological grounding

-

Reduced anticorrelation between DMN and task-positive networks

-

Network-level dysregulation rather than focal deficits

Clinical strength

Explains:

-

Mind-wandering

-

“Zoning out”

-

Task-unrelated thoughts

Limitation

Descriptive rather than mechanistic at the behavioral level.

6. Network Dysregulation Model (Contemporary View)

ADHD as large-scale network imbalance

Modern neuroimaging suggests ADHD is best understood as a disorder of network coordination, not isolated executive modules.

Key networks involved:

-

Frontoparietal control network

-

Salience network

-

Default mode network

-

Reward and motivational circuits

Core idea

ADHD reflects unstable switching and poor synchronization between networks required for sustained, goal-directed behavior.

This model integrates:

-

Executive deficits

-

Motivational variability

-

Emotional dysregulation

-

Context dependence

A unifying clinical insight

Across models, one theme recurs:

ADHD is not an absence of executive capacity, but an instability in executive control.

Patients can demonstrate:

-

Excellent performance under the right conditions

-

Severe impairment under low structure or low reward

This explains why ADHD often goes unrecognized in intelligent, high-functioning individuals—and why structure, interest, and immediacy can temporarily “normalize” functioning.

Implications for assessment and treatment

Understanding these models guides practice:

-

Assessment should go beyond attention tests to include:

-

Working memory

-

Inhibition

-

Delay tolerance

-

Emotional regulation

-

-

Treatment works best when it:

-

Enhances executive signaling (stimulants)

-

Modulates arousal and motivation

-

Adds external structure to compensate for internal instability

-

Trains executive endurance, not just speed

-

Closing reflection

ADHD is often misunderstood because it looks inconsistent. But inconsistency is the diagnosis.

Executive functioning in ADHD is not broken—it is context-sensitive, energy-dependent, and reward-responsive. The various models do not contradict each other; they describe different cross-sections of the same neurobiological reality.

Understanding these models allows clinicians to move from labeling deficits to designing environments where executive function can actually emerge.

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808