Antidepressants: Withdrawal, Relapse & the Right Way to Stop Medicines

This is one of the most common and most confusing questions patients ask.

This is one of the most common and most confusing questions patients ask.

Some people stop an antidepressant and feel almost nothing.

Others feel dizzy, anxious, restless, or unwell for a few days or weeks.

A small group feel much worse and begin to fear that something has gone permanently wrong with their brain.

So what is the truth?

Large scientific studies that carefully compared people stopping antidepressants with people stopping placebo show something reassuring:

For most people, stopping an antidepressant causes mild, short‑lived physical symptoms, usually peaking in the first 1–2 weeks and then fading away.

The most common symptoms are:

• Dizziness or light‑headedness

• Nausea

• Sleep disturbance

• Nervousness or anxiety

• Strange dreams

On average, people experience only one extra symptom compared to those stopping a placebo.

This means two things are true at the same time:

• Withdrawal symptoms are real.

• They are usually temporary and manageable.

But this is not the whole story.

Because what patients and doctors struggle with in real life is not just withdrawal.

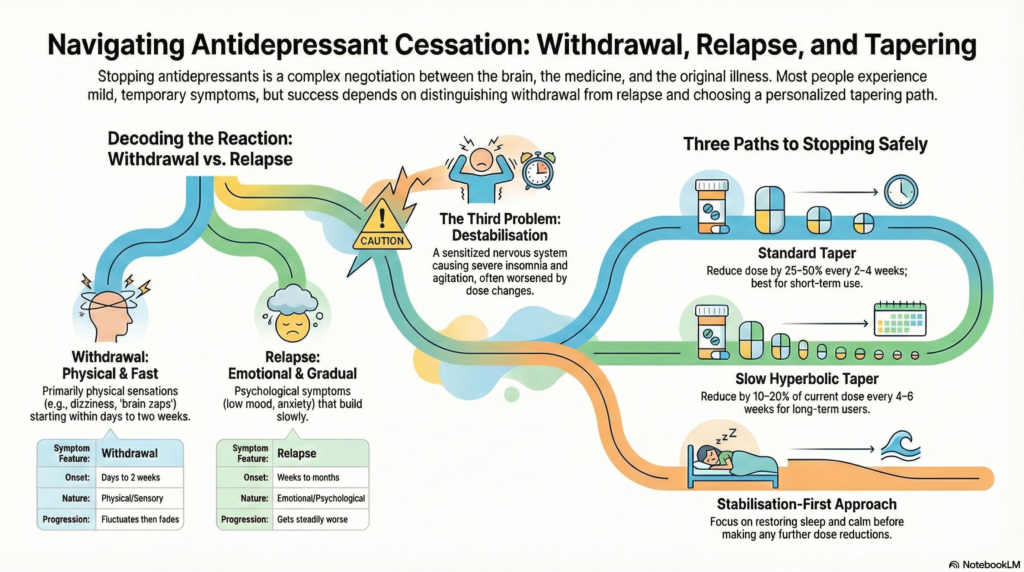

They struggle to tell apart three very different problems that can look similar:

• Withdrawal symptoms

• Relapse of the original illness

• A third problem: nervous system destabilisation during tapering

Once you can tell these apart, stopping antidepressants becomes far safer and far less frightening.

1. What is antidepressant withdrawal?

Withdrawal symptoms happen because the brain adjusts itself to the presence of a medicine. When the medicine is reduced or stopped, the brain needs time to rebalance.

This is not addiction. It is normal neuro‑adaptation.

Common withdrawal symptoms include:

• Dizziness or light‑headedness

• Nausea

• “Brain zaps” or electric‑shock sensations

• Flu‑like feelings

• Sleep disturbance

• Anxiety or nervousness

• Vivid or strange dreams

Large scientific studies show something important:

For most people, withdrawal symptoms are mild to moderate, start within a few days, peak in the first 1–2 weeks, and then fade away.

So two things are true at the same time:

• Withdrawal does exist.

• For most people, it is temporary and manageable.

Both extreme narratives — “withdrawal doesn’t exist” and “withdrawal destroys everyone’s life” — are inaccurate.

2. What is relapse, and how is it different from withdrawal?

Relapse means the return of the original illness — usually depression or an anxiety disorder.

This is where confusion causes real harm.

Withdrawal symptoms usually:

• Are mainly physical or strange body sensations

• Start within days to two weeks

• Fluctuate up and down

• Improve gradually even without treatment

Relapse symptoms usually:

• Are emotional and psychological

• Build slowly over weeks to months

• Get steadily worse

• Do not improve on their own

Careful research shows:

If low mood or anxiety appears months after stopping an antidepressant, it is almost always relapse — not withdrawal.

Why this matters:

• Mistaking relapse for withdrawal delays real treatment.

• Mistaking withdrawal for relapse leads to unnecessary lifelong medication.

3. The missing third problem: taper‑related destabilisation

A small group of people don’t fit neatly into either withdrawal or relapse.

They may taper slowly for months without trouble — and then suddenly feel much worse at a lower dose.

They develop:

• Severe insomnia

• Inner restlessness or agitation

• “Wired but tired” exhaustion

• Anxiety unlike their original illness

• Extreme sensitivity to tiny dose changes

Here’s the confusing part:

• Increasing the dose makes them worse.

• Reducing the dose further also makes them worse.

This is not typical withdrawal.

And it is not typical relapse.

It reflects a sensitised, over‑reactive nervous system.

In these cases, endlessly adjusting the antidepressant dose becomes a trap.

Sometimes tapering itself has become the main stressor.

4. Is slow tapering always safe?

You may have heard:

“Always taper extremely slowly. Use micro‑doses.”

This helps many people — but it is not harmless for everyone.

Very long tapers can:

• Keep people constantly watching their symptoms

• Increase fear and anticipation of problems

• Prolong physical instability

• Increase sensitivity to tiny dose changes

For a vulnerable minority, very slow tapering can actually make things worse.

So tapering is a treatment — not a moral rule.

And like all treatments, it has benefits and risks.

5. Three sensible ways to stop antidepressants

There is no single perfect taper.

The right method depends on the person.

A. Standard taper

Best for:

• Short‑term antidepressant use (under 1–2 years)

• First episode of depression

• No major anxiety disorder

• No past withdrawal problems

Typical method:

Reduce the dose by 25–50% every 2–4 weeks.

Most people do perfectly well with this.

B. Slow or hyperbolic taper

Best for:

• Long‑term use (over 3–5 years)

• Medicines like paroxetine or venlafaxine

• Past withdrawal symptoms

Typical method:

Reduce by 10–20% of the current dose every 4–6 weeks.

This creates smaller changes at lower doses.

C. Stabilisation‑first approach

Best for:

• People who worsen during taper

• People with severe insomnia or agitation

• People who feel worse both up and down

Here the priority is not the antidepressant dose.

It is restoring:

• Sleep

• Nervous system calm

• Emotional safety

Only after stability returns do we attempt further tapering.

6. The role of fear and online stories

Expectation changes how the brain feels symptoms.

When people are repeatedly told:

“This will permanently damage your nervous system,”

the brain’s danger circuits amplify every sensation.

This does not mean symptoms are imaginary.

It means fear is keeping the nervous system stuck in high‑alert mode.

Over‑medicalising every sensation as “protracted withdrawal” can trap people in disability.

7. A calm, balanced truth

Here is the reality that actually fits most lives:

• Withdrawal exists.

• Relapse exists.

• Taper‑related destabilisation exists.

Most people:

• Can taper in weeks to months.

• Have mild or moderate symptoms.

• Recover fully.

A minority:

• Need slow tapering.

• Need stabilisation before tapering.

• Need treatment beyond dose changes.

Dogma hurts patients.

Careful listening and individualised care heals them.

Final message

Stopping antidepressants is not a mechanical process.

It is a negotiation between:

• The medicine

• The brain

• The original illness

• The person’s fears and expectations

Good deprescribing is not just dose reduction.

It is real psychiatry.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808