Executive Dysfunction in the Era of Prolonged Digital Consumption

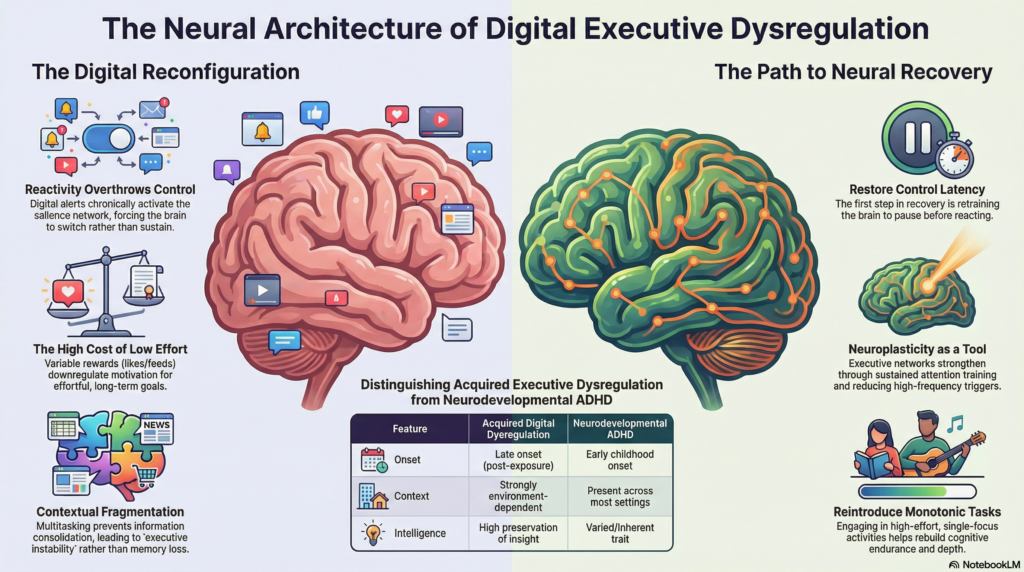

Executive dysfunction associated with prolonged digital consumption is often described in vague behavioral terms—poor focus, procrastination, mental fatigue, reduced productivity. While these descriptions are accurate, they risk obscuring a deeper truth: this phenomenon is best understood not as a failure of willpower or discipline, but as a predictable reconfiguration of large-scale brain networks under sustained environmental pressure.

Executive dysfunction associated with prolonged digital consumption is often described in vague behavioral terms—poor focus, procrastination, mental fatigue, reduced productivity. While these descriptions are accurate, they risk obscuring a deeper truth: this phenomenon is best understood not as a failure of willpower or discipline, but as a predictable reconfiguration of large-scale brain networks under sustained environmental pressure.

Modern digital environments do not merely distract the brain. They systematically bias how executive control networks develop, engage, and compete.

Executive function as a network property, not a single skill

Executive functions do not reside in a single “control center.” They emerge from coordinated activity across the frontoparietal control network (FPN), which includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, anterior cingulate, and their reciprocal connections with subcortical structures.

This network performs three core operations:

-

Maintaining task goals over time

-

Suppressing competing stimuli and impulses

-

Flexibly reallocating resources based on context

Crucially, executive control is metabolically expensive and therefore selectively engaged only when the brain deems it worthwhile.

The digital environment as a chronic salience manipulator

Digital platforms continuously stimulate the salience network, anchored in the anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. This network evolved to detect biologically relevant signals—novelty, threat, reward, social cues—and rapidly switch the brain’s state.

In digital contexts:

-

Notifications, alerts, infinite feeds, and short-form videos generate persistent salience signals

-

The salience network is chronically activated

-

The brain is repeatedly cued to switch, not sustain

Over time, this biases network dynamics away from the frontoparietal control network and toward stimulus-driven reactivity.

Dopamine, prediction error, and executive erosion

Dopamine is often misunderstood as a “pleasure chemical.” In reality, its primary role is prediction error signaling—flagging when something is better, worse, or more novel than expected.

Digital content exploits this mechanism precisely:

-

Variable reward schedules (likes, new posts, algorithmic feeds)

-

Rapid novelty turnover

-

Low-effort engagement with unpredictable outcomes

This leads to:

-

Preferential reinforcement of immediate, low-cost actions

-

Reduced tolerance for delayed or effortful rewards

-

Downregulation of motivation for sustained goal-directed tasks

Executive dysfunction emerges not because motivation disappears, but because the cost–benefit calculus of the brain shifts.

Working memory overload and contextual fragmentation

Working memory capacity is finite and tightly coupled to prefrontal function. Digital multitasking creates a state of contextual fragmentation, where information is constantly loaded and discarded without consolidation.

Neurobiologically:

-

Prefrontal neurons show reduced sustained firing

-

Information is processed shallowly, not integrated

-

The hippocampal–prefrontal dialogue weakens

The subjective experience is familiar:

“I know I read it, but it didn’t stick.”

“I can’t hold my thoughts long enough to plan.”

This is not memory loss—it is executive instability.

Inhibitory control: outpaced, not damaged

Inhibitory control depends on top-down prefrontal suppression of limbic and habitual responses. With prolonged digital exposure:

-

Bottom-up signals become faster and more frequent

-

Inhibitory circuits are repeatedly overridden

-

Reflexive checking behaviors become automatized

Importantly, there is no structural lesion. The system is intact but chronically outcompeted.

This explains why many individuals retain excellent performance in high-stakes, time-limited situations but struggle with self-directed, open-ended tasks.

Network competition: default mode vs executive control

Another underappreciated effect of digital overconsumption is altered interaction between the default mode network (DMN) and executive networks.

-

Rapid digital engagement fragments internal narrative

-

Mind-wandering becomes externally driven rather than reflective

-

DMN activity intrudes during tasks requiring focus

The result is a hybrid state: mentally busy, cognitively unproductive.

Clinical phenotype: acquired executive dysregulation

From a clinical standpoint, this pattern is best conceptualized as acquired executive dysregulation, distinct from:

-

Neurodevelopmental ADHD

-

Major depressive executive slowing

-

Neurodegenerative executive decline

Key features include:

-

Late onset

-

Strong context dependence

-

Preservation of intelligence and insight

-

Improvement with environmental and cognitive restructuring

This distinction matters diagnostically and therapeutically.

Neuroplasticity cuts both ways

The same plasticity that allows digital environments to reshape executive function also allows recovery.

Executive networks strengthen with:

-

Sustained attention training

-

Reduction of high-frequency salience triggers

-

Reintroduction of effortful, monotonic tasks

-

Structured goal hierarchies

-

Sleep normalization and circadian stability

What recovers first is control latency—the ability to pause before reacting. What follows is depth, endurance, and strategic thinking.

Broader implications

At a societal level, prolonged digital consumption does not make people unintelligent. It makes them reactive rather than deliberative.

Executive dysfunction in this context is not pathology—it is adaptation to an environment optimized for capture rather than control.

The clinical task is not to moralize or pathologize, but to help patients retrain their brains for agency in a world that constantly offers distraction.

Closing reflection

Executive function is the neural basis of authorship—of choosing what to attend to, what to ignore, and what to pursue over time.

When digital environments decide these things for us, executive control quietly atrophies—not through damage, but through disuse.

The goal of intervention is simple, though not easy:

to restore the brain’s ability to decide before it reacts.

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808