Withdrawal or Relapse – Drug Withdrawal or Relapse of Illness : A Critical Clinical Distinction

In psychiatric practice, one question quietly shapes diagnoses, treatment duration, and patient identity more than almost any other:

In psychiatric practice, one question quietly shapes diagnoses, treatment duration, and patient identity more than almost any other:

Is this a relapse of illness — or withdrawal from medication?

The two can look strikingly similar. Both may involve anxiety, low mood, insomnia, irritability, emotional dysregulation, or cognitive fog. Yet they arise from fundamentally different mechanisms and require very different clinical responses.

When withdrawal is mistaken for relapse, the consequences are not trivial. Patients may be labeled as chronically ill, medications may be restarted indefinitely, and attempts at recovery through deprescribing may be prematurely abandoned. Increasingly, contemporary research suggests this confusion is common — and avoidable.

Why the Confusion Exists

Psychotropic medications alter neurotransmitter systems and receptor dynamics. With long-term use, the brain adapts to their presence. When doses are reduced or stopped, the nervous system must recalibrate.

That recalibration can produce withdrawal syndromes — predictable, physiological responses that may closely resemble psychiatric symptoms.

Historically, psychiatry has tended to interpret symptom emergence after discontinuation as proof that the medication was “preventing relapse.” However, modern literature and deprescribing research challenge this assumption, demonstrating that withdrawal effects are frequently misclassified as relapse, both in clinical practice and in relapse-prevention trials.

Defining the Concepts Clearly

Withdrawal

Withdrawal refers to physiological and neuroadaptive symptoms that occur when a medication is reduced or stopped after sustained use.

-

Not addiction

-

Not misuse

-

A predictable biological response to neuroadaptation

Withdrawal has been well documented with antidepressants, benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, antipsychotics, and gabapentinoids.

Relapse

Relapse is the return of the underlying psychiatric disorder, reflecting illness vulnerability, psychosocial stressors, or incomplete recovery — independent of medication physiology.

Relapse is real and clinically important, but it must be diagnosed carefully.

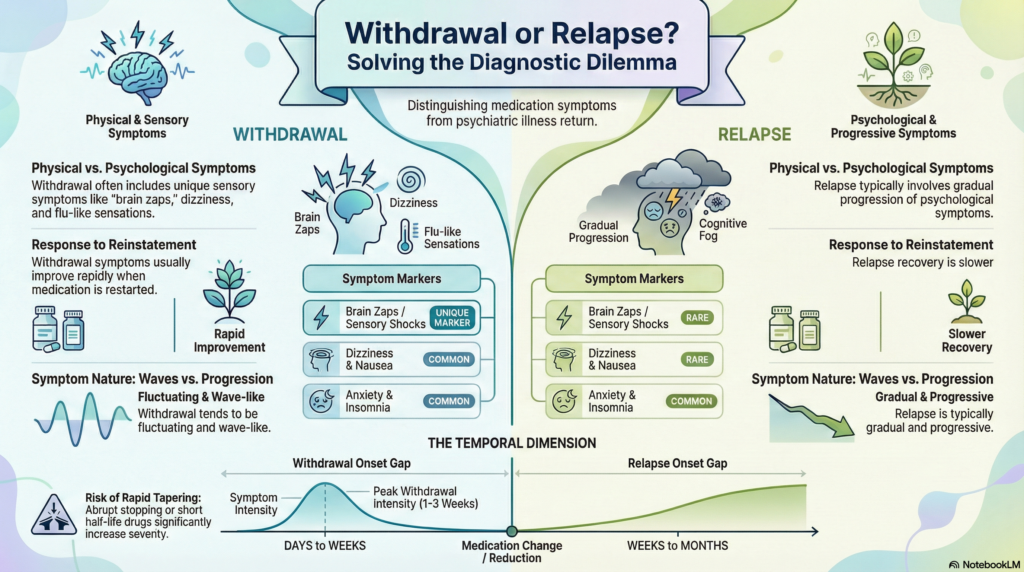

Withdrawal vs Relapse: Key Clinical Differences

| Feature | Withdrawal | Relapse |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Neurophysiological adaptation | Return of illness pathology |

| Onset | Days to weeks after dose reduction or cessation | Weeks to months (or longer) after recovery |

| Symptom course | Fluctuating, wave-like | Gradual, progressive |

| Physical symptoms | Common (dizziness, nausea, sensory disturbances) | Uncommon |

| Emotional lability | Prominent | Present but illness-patterned |

| Response to reinstatement | Often rapid improvement | Slower, requires sustained treatment |

| Relation to dose changes | Strong temporal link | Often unrelated |

Symptom Patterns: Where They Overlap and Diverge

| Symptom | Withdrawal | Relapse |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ✓ | ✓ |

| Low mood | ✓ | ✓ |

| Insomnia | ✓ | ✓ |

| Irritability | ✓ | ✓ |

| “Brain zaps” / sensory shocks | ✓ | Rare |

| Dizziness / flu-like symptoms | ✓ | Rare |

| Cognitive fog | ✓ | Sometimes |

| Return of original syndrome pattern | Sometimes | ✓ |

The presence of physical and sensory symptoms, especially soon after dose changes, strongly points toward withdrawal rather than relapse.

Timelines Matter: Understanding When Symptoms Appear

Typical Withdrawal Timeline

| Phase | Timeframe | Common Features |

|---|---|---|

| Early | 1–7 days | Dizziness, nausea, anxiety, insomnia |

| Peak | 1–3 weeks | Emotional lability, sensory symptoms, agitation |

| Resolution | 2–12 weeks | Gradual improvement with stable taper |

| Protracted withdrawal | >3 months | Persistent symptoms in a minority |

Withdrawal timelines vary widely, influenced by drug half-life, duration of use, taper speed, and individual neurobiology.

Typical Relapse Timeline

| Phase | Timeframe | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Early vulnerability | Weeks to months | Gradual mood or anxiety changes |

| Progressive relapse | Months | Increasing functional impairment |

| Full relapse | Variable | Syndrome resembles original illness |

Relapse rarely begins immediately after dose reduction and usually lacks prominent somatic features.

Risk Factors That Increase Withdrawal Severity

| Factor | Effect |

|---|---|

| Long duration of use | ↑ Withdrawal risk |

| High receptor occupancy drugs | ↑ Severity |

| Short half-life medications | ↑ Intensity |

| Rapid or abrupt stopping | Major risk |

| Previous failed discontinuations | ↑ Sensitivity |

| High baseline anxiety | Amplifies symptoms |

Why Mislabeling Withdrawal as Relapse Causes Harm

When withdrawal is mistaken for relapse:

-

Patients are told their condition is lifelong

-

Medications are restarted indefinitely

-

Deprescribing attempts are abandoned

-

Diagnostic certainty becomes inflated

-

Patient trust erodes

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle:

withdrawal → misdiagnosis → chronic prescribing

Over time, pharmacological dependence is mistaken for disease chronicity.

Clinical Implications: A Shift in Thinking

The most important change is conceptual.

Instead of asking:

“Is this relapse?”

Clinicians should first ask:

“Could this be withdrawal?”

This reframing:

-

Reduces unnecessary long-term medication

-

Strengthens therapeutic alliance

-

Aligns practice with emerging evidence

-

Respects patient experience

Careful tapering, close monitoring, and collaborative decision-making are central to this approach.

Conclusion

This is not an argument against psychiatric medication. It is an argument for precision, humility, and clinical accuracy.

Good psychiatry knows when to prescribe.

Excellent psychiatry also knows when — and how — to stop.

As long-term psychotropic use continues to rise globally, the ability to distinguish withdrawal from relapse is no longer optional. It is a core clinical skill and an ethical responsibility.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808