Social Media Use and the Adolescent Brain: Why Patterns Matter More Than Screen Time

For more than a decade, discussions about adolescents and screens have gone in circles. One camp insists social media is damaging a generation; the other argues there’s no solid evidence of harm and that concern is just moral panic dressed up as science.

For more than a decade, discussions about adolescents and screens have gone in circles. One camp insists social media is damaging a generation; the other argues there’s no solid evidence of harm and that concern is just moral panic dressed up as science.

The truth is quieter—and more useful.

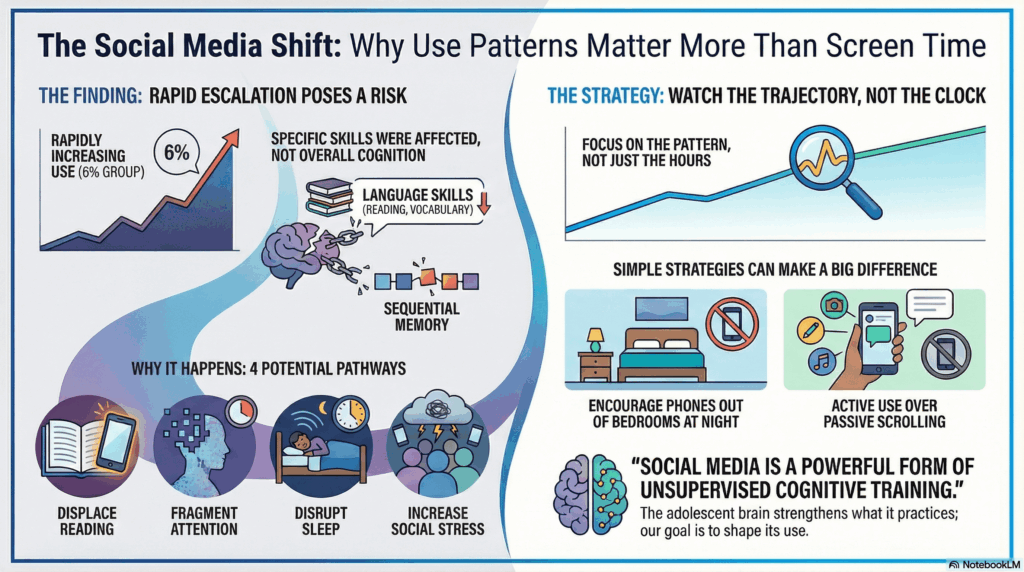

A recent study published in JAMA shifts the conversation in an important way. Instead of asking how much social media adolescents use, it asks how their use changes over time. That change in perspective—from hours to trajectories—turns out to matter.

Moving beyond “How many hours?”

Most screen-time research treats usage as static. Two hours today is treated the same as two hours next year. But adolescent development is dynamic. Brains respond not just to exposure, but to patterns of engagement over time.

The 2025 JAMA study followed more than 6,500 children from around age 9–10 years for two years and identified three social media use trajectories:

-

A majority with little to no use, remaining stable

-

A large group with gradually increasing use

-

A small but important group with rapidly increasing use

It was this last group—about 6% of the sample—that stood out.

What did the study actually find?

At follow-up, cognition was assessed using standardized tools measuring language, memory, and processing speed. Adolescents whose social media use increased rapidly showed slightly lower performance in:

-

Language skills (reading and vocabulary)

-

Sequential memory

The differences were small, not dramatic. There was no evidence of global cognitive decline, and processing speed was unaffected. This matters, because it tells us the association is selective, not sweeping.

In simple terms, the study does not say social media ruins cognition. It suggests that certain developmental patterns of use may be associated with subtle differences in how language and memory develop.

Why might rising social media use affect language and memory?

Because this was an observational study, causation cannot be established. Still, several plausible pathways are worth considering.

One is displacement. Language development depends on reading, conversation, and sustained engagement with text. When social media use expands rapidly, something else often contracts—and reading time is a common casualty.

Another factor is attention fragmentation. Social platforms reward novelty, rapid switching, and constant feedback. Over time, this may shape attentional habits that are less suited to deep reading and memory consolidation.

Sleep is also central. Escalating use frequently creeps into late evenings. Even mild, chronic sleep restriction impairs learning and memory long before it affects mood.

Finally, there is social stress. For some adolescents, social media becomes a continuous evaluation environment. Chronic social comparison and interpersonal stress reliably interfere with cognitive performance.

None of these require social media to be “bad.” They reflect a mismatch between adolescent neurodevelopment and environments optimized for engagement rather than growth.

Why this matters for policy, not just parents

A companion JAMA editorial published alongside the study reframes the debate. Instead of asking whether social media is good or bad, it asks: What level of evidence is sufficient to justify protective action?

Public health rarely waits for perfect certainty. Seat belts, tobacco warnings, and lead regulations were implemented when evidence was strong enough—not complete.

Social media exposure is nearly universal, developmentally timed, and commercially driven. Even small cognitive effects, when spread across millions of adolescents, become meaningful at a population level.

This is why recent discussions emphasize risk reduction and accountability, not bans or panic.

What this means in practice

The most important takeaway is not to count hours obsessively, but to watch trajectories.

Rapid escalation of use—especially when accompanied by sleep disruption, declining reading, irritability, or loss of control—deserves attention and support.

Helpful strategies are often simple:

-

Phones out of bedrooms at night

-

Clear digital “wind-down” times

-

Fewer notifications and less autoplay

-

Emphasizing active use over passive scrolling

For adolescents with ADHD, anxiety, or mood disorders, intentional structure matters even more.

The bigger picture

The adolescent brain is not fragile—but it is plastic. What it practices, it strengthens.

Social media is best understood as a powerful, unsupervised form of cognitive training. The real challenge is not whether adolescents will use it, but whether we will shape how they use it while development is still underway.

References

-

Nagata JM, Wong JH, Kim KE, et al. Social media use trajectories and cognitive performance in adolescents. JAMA. 2025;334(21):1948-1950.

-

Madigan S, Yeates KO, Fearon P. Developmental costs of youth social media require policy action. JAMA. 2025;334(21):1891-1892.

-

Office of the Surgeon General. Social media and youth mental health: advisory. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2023.

-

Chen Y, Yim H, Lee TH. Negative impact of daily screen use on inhibitory control networks in preadolescence: a 2-year follow-up study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2023;60:101218.

-

Boer M, Stevens GWJM, Finkenauer C, van den Eijnden RJJM. The course of problematic social media use in young adolescents. Child Dev. 2022;93(2):e168-e187.

About the author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi)

Neurofeedback Specialist

Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall), Chennai

Dr. Srinivas works at the intersection of clinical psychiatry, neurocognition, and digital mental health. His work focuses on evidence-based assessment of attention, sleep, and emotional regulation in children and adolescents, integrating clinical care with emerging neuroscience and technology.

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808