Key Concepts in Antidepressant Withdrawal

Antidepressant withdrawal is one of the most misunderstood topics in modern psychiatry.

Antidepressant withdrawal is one of the most misunderstood topics in modern psychiatry.

Some people are told it doesn’t exist.

Others are told it permanently damages the brain.

Both ideas are wrong.

What actually happens is more human, more biological, and far more hopeful.

This article explains the key concepts behind antidepressant withdrawal in simple language — without fear, ideology, or denial.

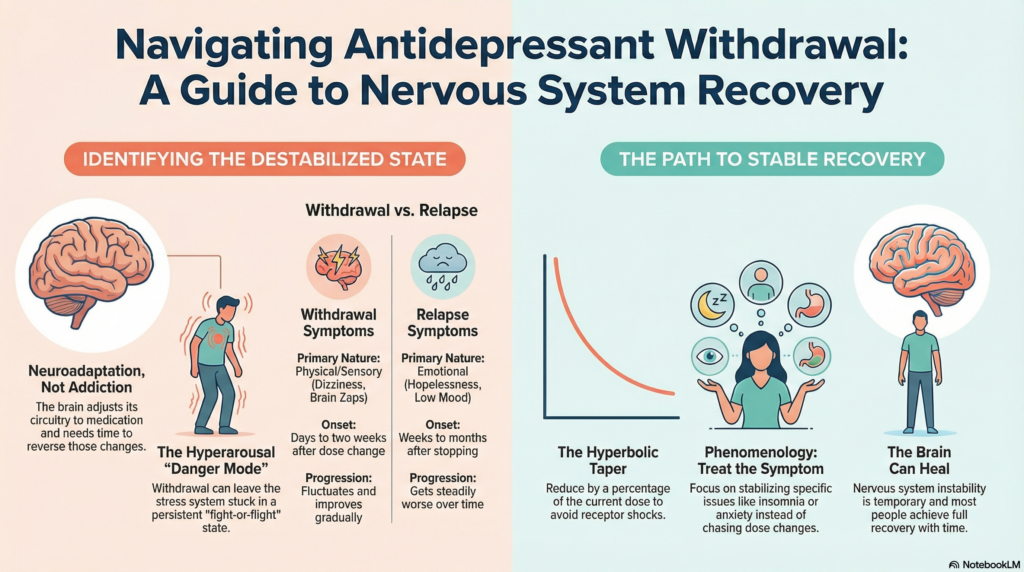

1) Neuroadaptation — Why Withdrawal Happens at All

When you take an antidepressant for weeks or months, your brain adjusts to it.

It changes receptor sensitivity, chemical balance, and circuit activity to maintain stability.

This process is called neuroadaptation.

When the drug is reduced or stopped, the brain needs time to reverse those changes.

Withdrawal symptoms are simply the brain saying:

“I need time to rebalance.”

This is not addiction.

It is normal biology.

2) Withdrawal vs Relapse — Two Very Different Things

This is the most important distinction of all.

Withdrawal symptoms usually:

• Are physical or sensory (dizziness, nausea, brain zaps)

• Start within days to two weeks

• Fluctuate up and down

• Improve gradually on their own

Relapse symptoms usually:

• Are emotional and psychological (low mood, hopelessness, panic)

• Build slowly over weeks to months

• Get steadily worse

• Do not improve spontaneously

If depression or anxiety appears months after stopping medication, it is almost always relapse — not withdrawal.

3) Hyperbolic Taper — Why Tiny Dose Changes Matter

At high doses, big milligram changes barely affect the brain.

At low doses, tiny milligram changes can have large effects.

This is because the drug’s effect on brain receptors is non‑linear.

A hyperbolic taper means reducing by a percentage of the current dose rather than a fixed number of milligrams.

Example:

10 mg → 8 mg → 6.5 mg → 5 mg → 4 mg → 3 mg → 2 mg → 1 mg

This creates gentler changes at the lower end.

4) Sensitisation — When the Brain Becomes Over‑Reactive

In some people, repeated dose changes act like repeated stress.

The nervous system becomes sensitised.

That means:

• Small changes feel huge

• Normal sensations feel unbearable

• Sleep and anxiety become unstable

This is why some people worsen with both dose increases and dose decreases.

5) Hyperarousal — The Nervous System Stuck in Danger Mode

Some people in withdrawal feel:

• Wired but exhausted

• Restless inside

• Unable to relax

• Unable to sleep deeply

This is called hyperarousal.

It means the brain’s stress system is stuck in “fight‑or‑flight” mode.

6) Noradrenergic Disinhibition — The Adrenaline Surge

Antidepressants dampen certain stress circuits.

When the dose is reduced, that calming brake can suddenly lift.

This causes over‑activity of the brain’s adrenaline‑like system.

Common symptoms

• Early‑morning dread

• Racing heart

• Sweating

• Inner agitation

• Panic‑like feelings

7) Limbic System Hyperreactivity — The Emotional Alarm Misfiring

The limbic system is the brain’s emotional alarm centre.

In withdrawal, it can become too sensitive.

Neutral sensations are interpreted as danger.

This creates:

• Sudden anxiety spikes

• Fear without a clear reason

• Emotional instability

8) REM Rebound — Why Sleep Becomes Strange

REM sleep is the dream stage of sleep.

Antidepressants suppress REM sleep.

When the drug is reduced, REM sleep rebounds too strongly.

This causes:

• Vivid dreams or nightmares

• Light, unrefreshing sleep

• Early‑morning waking

Poor sleep then worsens anxiety and mood.

9) Reinstatement — Why Going Back Up Doesn’t Always Help

Reinstatement means increasing the antidepressant dose again after symptoms appear.

In early withdrawal, this often helps.

But in a sensitised brain, reinstatement can sometimes worsen symptoms — just like starting an antidepressant can initially increase anxiety.

10) Protracted Withdrawal — A Misleading Label

This term means withdrawal symptoms that last for many months or longer.

Sometimes this is true.

But sometimes the problem is no longer withdrawal at all.

It is a new state of nervous‑system destabilisation.

Calling everything “protracted withdrawal” can block proper treatment.

11) Phenomenology — Treat What Is Actually Happening

Phenomenology is a simple but powerful idea.

It means:

Carefully describing what the person is actually experiencing right now — without forcing it into a label.

Instead of immediately deciding:

• “This is withdrawal.”

• “This is relapse.”

• “This is permanent damage.”

We slow down and ask:

• What exactly are the symptoms right now?

• Is this insomnia, anxiety, agitation, low mood, dizziness, or panic?

• When did each symptom start?

• What makes it better or worse?

Why this matters:

Withdrawal, relapse, and nervous‑system destabilisation can look similar on the surface — but they behave very differently.

If we treat everything as “withdrawal,” we keep adjusting the antidepressant dose.

If we treat everything as “relapse,” we keep increasing medication.

Both approaches can fail.

12) How Returning to Phenomenology Improves Recovery

When someone is stuck in a difficult taper, the real problem is often no longer the antidepressant dose.

It is the state the nervous system has shifted into.

This state may include:

• Severe insomnia

• Hyperarousal or inner agitation

• Panic‑like anxiety

• Emotional volatility

• Exhaustion and fear

A phenomenology‑based approach changes the entire treatment strategy.

Instead of asking only:

“Should we go up or down on the antidepressant?”

We ask:

• What symptom is causing the most suffering right now?

• Is sleep the main driver of everything else?

• Is anxiety being maintained by hyperarousal?

• Is fear amplifying bodily sensations?

Then we treat that symptom directly.

Examples

• If insomnia is dominant → prioritise sleep stabilisation.

• If hyperarousal is dominant → calm the stress system.

• If panic is dominant → reduce threat‑prediction and fear loops.

• If low mood is dominant → treat depression as depression.

This breaks the endless cycle of dose changes.

13) Why Labels Can Trap People

Labels can validate suffering — but they can also trap people.

When everything is called:

• “Protracted withdrawal”

• “Permanent nervous‑system damage”

Patients feel hopeless.

Clinicians feel helpless.

No new treatment ideas appear.

Phenomenology restores movement.

It reminds us that:

The cause of suffering is not always what is maintaining it.

Withdrawal may have started the problem.

But insomnia, hyperarousal, fear, and sensitisation may now be keeping it alive.

Those are all treatable.

14) Nocebo Effect — When Fear Amplifies Symptoms

The nocebo effect is the opposite of placebo.

If people strongly expect harm, the brain amplifies symptoms.

This does not mean symptoms are fake.

It means expectation changes brain chemistry and perception.

15) Allostatic Load — When Stress Overloads the Brain

This means the total stress burden on the nervous system.

Withdrawal + sleep loss + fear + life stress = too much load.

When the load is too high, the brain destabilises.

16) Akathisia‑Like Agitation — Inner Restlessness

Akathisia means unbearable inner restlessness.

People feel:

• They must keep moving

• They cannot sit still

• They feel trapped inside their body

This can happen during difficult tapers.

17) Threat‑Prediction Circuits — The Anxious Brain Loop

The brain constantly predicts danger.

When these circuits are overactive, the brain assumes something is wrong even when it isn’t.

This keeps anxiety and physical symptoms going.

Final Message

All these terms describe different parts of the same problem:

A nervous system that has become temporarily over‑reactive and unstable during antidepressant tapering.

This state is not permanent.

The brain can heal.

With calm guidance, sleep stabilisation, reduced fear, and sensible tapering, most people recover fully.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91‑8595155808