Dementia: A Practical Guide for Caregivers

Behavioural symptoms, communication, burnout prevention, and dignity-focused care

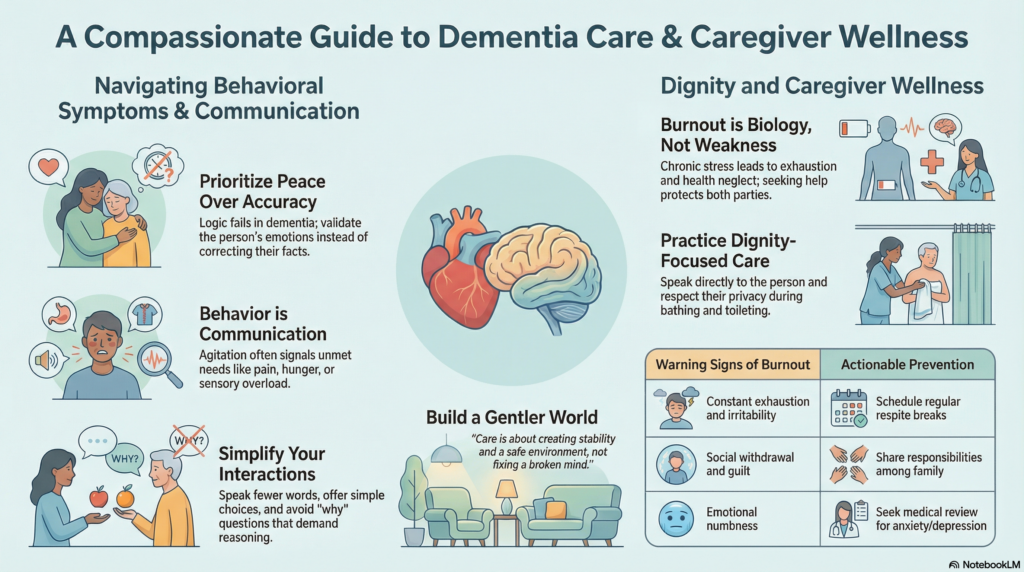

Caring for a person with dementia is not only about memory loss. It is about navigating changed behaviour, altered emotions, disrupted communication, and gradual role reversal—often while the caregiver’s own life quietly shrinks around the illness.

This guide is written for caregivers who want clarity without complexity, and science without coldness.

Dementia is not just memory loss

Most people associate dementia with forgetting names or repeating questions. But what strains families the most are behavioural and psychological symptoms, often called BPSD.

These may include:

-

Agitation, restlessness, or pacing

-

Irritability or sudden anger

-

Suspicion, fear, or false beliefs

-

Sleep–wake reversal

-

Apathy or emotional withdrawal

These behaviours are not intentional. They are expressions of a brain struggling to interpret the world.

The goal of caregiving is not to “correct” the person—but to reduce distress.

Understanding behavioural symptoms: what’s really happening?

Behavioural symptoms usually arise from one or more of the following:

-

Unmet needs

Pain, hunger, constipation, infection, poor sleep, or sensory overload. -

Cognitive mismatch

The environment demands skills the brain no longer has—time awareness, judgment, sequencing. -

Emotional memory remains intact

Even when factual memory fades, the feeling of fear, shame, or safety remains strong.

Before reacting to behaviour, pause and ask:

“What might they be trying to communicate?”

This simple shift prevents many confrontations.

Communication: stop arguing with the illness

One of the hardest lessons for caregivers is this:

Logic does not work in dementia.

Correcting, confronting, or proving facts often escalates distress.

Principles of dementia-friendly communication

-

Slow down: Speak fewer words, not louder words

-

Validate emotion, not facts

“I see you’re worried” works better than “That’s not true” -

Offer choices, not commands

“Would you like tea or water?” instead of “Drink this” -

Avoid ‘why’ questions

They demand reasoning the brain can no longer perform

When a person insists on something untrue, ask:

“Is correcting this helping—or hurting?”

Peace is often more therapeutic than accuracy.

Managing common behavioural challenges

Agitation and restlessness

Often linked to anxiety, pain, or boredom.

Helpful strategies:

-

Gentle routine and predictability

-

Short walks or light physical activity

-

Soft music or familiar sounds

-

Checking for pain, urinary issues, constipation

Medication is not the first solution. Environment and reassurance matter more.

Sleep disturbances

Common due to circadian rhythm disruption.

Practical steps:

-

Daytime sunlight exposure

-

Avoid long daytime naps

-

Quiet evenings, dim lights after sunset

-

Consistent bedtime routine

Sedatives should be used cautiously and only under medical guidance.

Suspicion or paranoia

Arguing worsens fear.

Instead:

-

Reassure safety

-

Avoid validating false beliefs directly

-

Redirect attention gently

Example:

“I’ll stay with you. You’re safe.”

Dignity-focused care: the ethical core of caregiving

Dementia slowly strips away independence—but dignity must never be optional.

Dignity-focused care means:

-

Speaking to the person, not about them

-

Avoiding infantilising language

-

Respecting privacy during bathing and toileting

-

Including them in decisions at whatever level remains possible

Even in advanced stages, the person is still present—emotionally, relationally, humanly.

Caregiver burnout: the invisible crisis

Caregivers often minimise their own suffering:

“Others have it worse.”

“This is my duty.”

But burnout is not weakness—it is biology and chronic stress.

Warning signs include:

-

Constant exhaustion

-

Irritability or guilt

-

Emotional numbness

-

Social withdrawal

-

Health neglect

A burned-out caregiver cannot provide good care.

Preventing caregiver burnout (this is not selfish)

Burnout prevention is care planning, not indulgence.

Practical steps:

-

Scheduled respite, even short breaks

-

Sharing responsibility—no single caregiver should do everything

-

Clear role division among family members

-

Medical review when depression or anxiety emerges

Seeking help early protects both the caregiver and the patient.

When medications are needed

Medications may help when:

-

Behaviour causes harm or severe distress

-

Non-pharmacological measures fail

-

Sleep or agitation threatens safety

They should be:

-

Used at the lowest effective dose

-

Reviewed regularly

-

Never used simply for convenience

Good dementia care is not about sedation, but stability.

What good dementia care really looks like

Good care is not dramatic. It is quiet, repetitive, patient.

It looks like:

-

Reduced distress

-

Fewer confrontations

-

Safer routines

-

A caregiver who is still functioning as a human being

Dementia cannot yet be cured—but suffering can be reduced.

Final thought

Dementia care is not about fixing a broken mind.

It is about building a gentler world around a vulnerable brain.

Small changes, done consistently, matter more than heroic effort.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808