Developmental assessment in Neurodevelopmental disorders ( ADHD & Autism)

Developmental Assessment : ADHD and Autism: where they converge, where they diverge, and how to assess them sensibly

Developmental Assessment : ADHD and Autism: where they converge, where they diverge, and how to assess them sensibly

In real clinics (especially in India), children rarely arrive with textbook symptoms. They arrive with complaints:

-

“Not listening / not sitting.”

-

“Speech is delayed.”

-

“Tantrums.”

-

“Poor handwriting.”

-

“Not mixing with other kids.”

-

“Screen addiction.”

-

“Teacher says ADHD.”

-

“Grandparents say he’ll grow out of it.”

Your job in developmental assessment is not to pick a label quickly. It’s to map a child’s developmental profile—strengths, delays, regulatory style, and functional impact—then decide what explains the pattern best and what support will help the child now.

ADHD and autism often co-occur, frequently overlap in surface behaviours, and can mask each other. A good assessment separates what the child can’t do yet from what the child won’t do from what the environment is making harder than it needs to be.

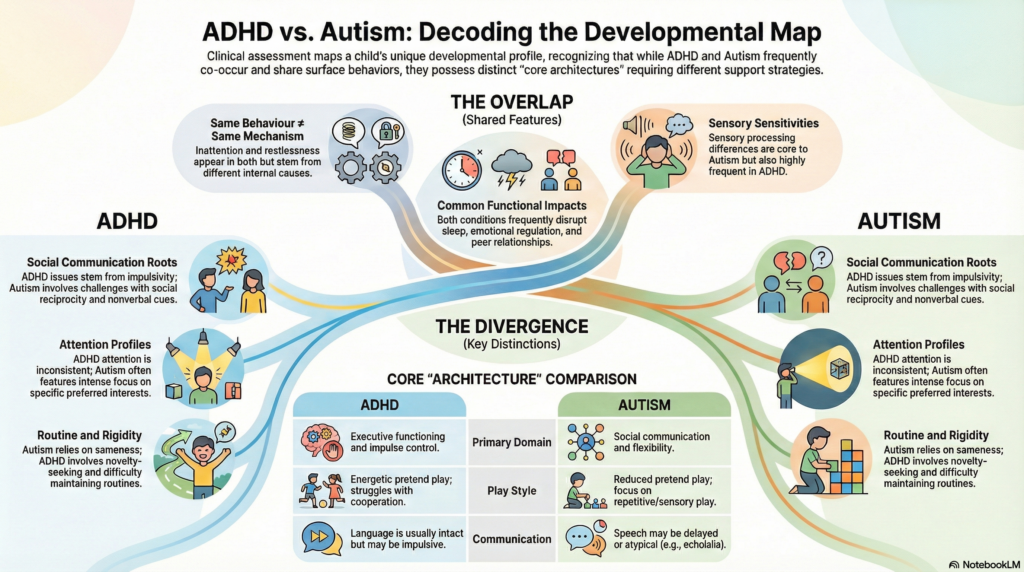

The “core architecture”

What’s centrally different in ADHD vs Autism

A useful way to remember it:

ADHD is primarily a disorder of attention regulation, impulse control, and activity level (executive functioning).

Autism is primarily a disorder of social communication development + restricted/repetitive patterns + sensory processing differences (developmental social brain + flexibility).

They can look similar because both affect:

-

classroom functioning,

-

emotional regulation,

-

peer relationships,

-

sleep,

-

and family stress.

But the reason underneath is often different.

Where they converge

Shared features that confuse everyone

These are common in both ADHD and autism (and in many other conditions too), so they are not diagnostic by themselves:

-

Inattention (for different reasons: distractibility vs social/communication load vs sensory overload)

-

Restlessness / fidgeting

-

Emotional outbursts / low frustration tolerance

-

Sleep problems

-

Sensory sensitivities (common in autism, also frequent in ADHD)

-

Social difficulties (impulsivity can look like “poor social skills”; autism can look like “doesn’t care”)

-

Rigid behaviour (ADHD can be oppositional from poor inhibition; autism can be true cognitive inflexibility)

-

Academic issues (especially writing, math, reading comprehension, exam behaviour)

So the clinician’s mantra is:

Same behaviour ≠ same mechanism.

Where they diverge

Clues that push you toward one or the other (or both)

1) Social communication

-

Autism: difficulty with social reciprocity (back-and-forth), nonverbal communication, understanding social context, joint attention (especially earlier in life).

-

ADHD: social issues are often from impulsivity, interrupting, missing cues due to distraction—but the child generally wants social connection and understands it when slowed down.

2) Restricted/repetitive behaviours

-

Autism: stereotypies, intense circumscribed interests, strong insistence on sameness, repetitive play themes, sensory seeking/avoidance patterns.

-

ADHD: novelty seeking is more typical; routines are hard to maintain (though anxiety can create rigidity).

3) Attention profile

-

ADHD: attention is inconsistent across almost everything; sustained attention is hard even for preferred tasks (except “hyperfocus” episodes).

-

Autism: attention may be very strong for preferred interests; difficulty may appear more in social attention, shifting attention, or tasks with ambiguity.

4) Communication development

-

Autism: early gesture use, joint attention, pragmatic language are key; speech can be delayed or atypical (echolalia, pedantic speech).

-

ADHD: language is usually developmentally intact, though the child may speak impulsively, talk excessively, or be disorganized.

5) Play

-

Autism: reduced pretend play, more repetitive/sensory play, difficulty with shared imaginative play.

-

ADHD: pretend play is usually present and energetic; difficulty is in sustaining/cooperating due to impulsivity.

The developmental assessment: a stepwise framework

Step 1: Define the referral question—and translate it into domains

Parents come with symptoms; schools come with complaints. Convert both into domains:

-

attention/executive functioning

-

activity/impulsivity

-

language (expressive/receptive/pragmatic)

-

social reciprocity and nonverbal communication

-

play and peer functioning

-

learning and academics

-

motor coordination and handwriting

-

sensory profile

-

emotion regulation and behaviour

-

sleep, screens, diet routines

-

family stressors and parenting responses

This ensures you don’t do a “diagnosis hunt.” You do a development map.

Step 2: A proper developmental history (the highest-yield tool)

Key anchors (especially relevant in Indian settings where histories are rich):

-

Pregnancy/perinatal: prematurity, NICU stay, seizures, jaundice, significant complications

-

Early milestones: sitting, walking, first words, two-word phrases

-

Red flags: loss of skills at any age

-

Social milestones: response to name, pointing, showing, shared enjoyment

-

Language quality: gestures, echolalia, conversational reciprocity

-

Behavioural style: adaptability, transitions, routine dependence

-

Sensory: food selectivity, clothing sensitivity, noise intolerance, seeking pressure/spinning

-

School functioning: teacher reports across settings (classroom vs tuition vs home)

-

Family history: ADHD, autism traits, learning disorders, mood/anxiety, epilepsy

-

Screens: timing, duration, role in regulation (screens can amplify symptoms but rarely explain the whole pattern)

Step 3: Observe—not just what the child does, but how they respond to you

In-clinic observation is powerful when you watch for:

-

joint attention (looks where you point? points to show?)

-

social reciprocity (back-and-forth affect, shared enjoyment)

-

nonverbal communication (gestures, facial expression, coordinated gaze)

-

response to name

-

quality of play (pretend play? functional play? repetitive play?)

-

flexibility (how do transitions go?)

-

sensory regulation (covering ears, seeking movement, scanning)

-

attention style (distractible vs absorbed; shifting ability)

-

impulsivity (grabbing, interrupting, unsafe climbing)

Step 4: Multi-informant, multi-setting data (mandatory for ADHD)

For ADHD especially, impairment must be present across settings. In India, many children are “fine at home” but struggling at school—or vice versa.

Collect:

-

teacher narratives (not just “hyperactive”)

-

notebooks and exam sheets

-

report cards with remarks

-

tuition teacher inputs

-

school counsellor notes (if available)

Step 5: Use rating scales as instruments—not as verdicts

Commonly used (choose depending on age and context):

-

ADHD: Vanderbilt / Conners / SNAP-IV

-

Autism screening: M-CHAT-R/F (toddlers), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2)

-

Adaptive functioning: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (if accessible)

-

Behaviour/emotions: CBCL, SDQ

-

Sensory: Sensory Profile questionnaires

-

Executive function: BRIEF (where feasible)

Scales quantify severity and monitor change, but diagnosis still rests on clinical synthesis.

Step 6: Rule-outs and “look-alikes” (the differential diagnosis checkpoint)

For autism-like presentations

-

hearing impairment (always check)

-

language disorder (especially pragmatic language)

-

intellectual disability/global developmental delay

-

trauma/neglect, attachment disruption

-

severe anxiety/selective mutism

-

epilepsy syndromes and regression conditions (if regression present)

For ADHD-like presentations

-

sleep deprivation (common in Indian households with late-night screens)

-

anxiety, depression (in older children)

-

learning disorder (child “acts out” to avoid failure)

-

thyroid issues, anemia, seizure disorders (as clinically indicated)

-

high screen exposure with poor structure (can mimic attention problems)

Step 7: Formulation, not just diagnosis

A good assessment ends with:

-

diagnoses (if criteria met),

-

comorbidities,

-

functional impairments,

-

protective factors (strengths),

-

and a staged intervention plan.

Often the most accurate conclusion is not “ADHD vs autism,” but:

“Neurodevelopmental profile consistent with ADHD with pragmatic language weakness and sensory dysregulation”

or

“Autism with prominent inattention and hyperactivity (possible comorbid ADHD).”

The overlap reality: ADHD + Autism together

Modern practice accepts that ADHD and autism commonly co-occur. When both are present:

-

ADHD symptoms can make autism supports harder to deliver (child can’t sit for therapy)

-

autism-related sensory overload can look like “worsening ADHD”

-

anxiety is frequently the hidden amplifier

Treatment planning becomes layered: sleep + sensory + structure first, then targeted therapies, then medications as needed.

A clinician-friendly “quick distinction” lens

When you’re stuck, ask:

-

Is the main issue regulating attention/impulses (ADHD), or understanding/participating in social communication + rigidity/sensory (autism)?

-

Does the child struggle socially because of speed and impulsivity, or because of social cognition and reciprocity?

-

Is the child rigid because of anxiety/poor inhibition, or because of true inflexibility and need for sameness?

-

Is the child’s language issue delay, pragmatics, or both?

Indian context: practical realities that matter

A few India-specific factors that can distort assessment unless you explicitly account for them:

-

High family scaffolding: adults anticipate needs, speak for the child, reduce social demands → delays become visible late.

-

Tuition culture: child may appear “okay” in 1:1 tuition but fail in classroom demands → setting effect.

-

Bilingual/multilingual exposure: normal language mixing vs true language delay needs careful differentiation.

-

Late sleep + screens: chronic sleep debt can mimic ADHD and worsen autism dysregulation.

-

Stigma and denial: families delay assessment fearing “label,” but early support helps most when started early.

End point: what a good assessment should produce

A well-done developmental assessment should leave parents with:

-

clarity about what is happening,

-

a plan for school and home,

-

and realistic hope grounded in action.

A label is not the end. It’s the beginning of tailored support.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808

Dr. Srinivas works with children, adolescents, and families, focusing on developmental assessments for ADHD, autism and related neurodevelopmental concerns, caregiver guidance, school coordination, and evidence-based interventions—translated into practical steps that fit real Indian homes and classrooms.

Early clarity empowers families. Early support shapes futures.