How Can We Conceptualize Behavioural Addiction Without Pathologizing Common Behaviours?

In everyday clinical practice, one question keeps resurfacing:

“Doctor, am I addicted to this?”

The behaviour may be gaming, phone use, pornography, shopping, work, or online trading. What the person is really asking is not about a label. They are asking whether something ordinary has crossed an invisible line into illness.

This is precisely where psychiatry must balance clarity with restraint.

What DSM-5 Actually Says—and What It Deliberately Avoids

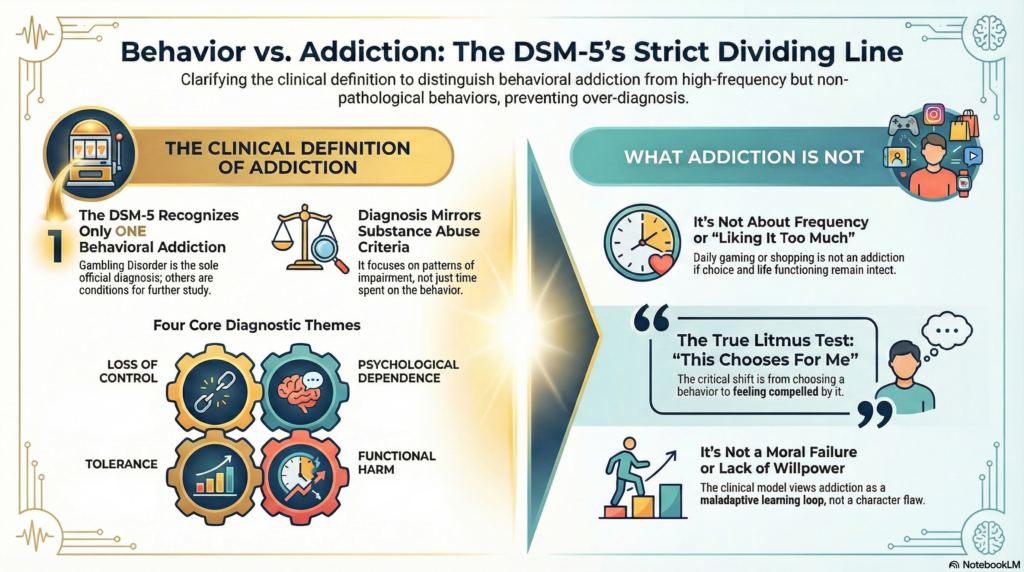

A useful starting point is a common misconception: DSM-5 does not recognise multiple behavioural addictions.

In fact, DSM-5 formally includes only one behavioural addiction:

-

Gambling Disorder

Other behaviours—gaming, internet use, pornography, shopping—are discussed cautiously, either in research sections or under “conditions for further study” (as gaming disorder later appears in ICD-11, not DSM-5).

This restraint is intentional. DSM-5 avoids pathologising everyday behaviours unless there is strong evidence of a syndrome that mirrors substance addiction in structure, not just intensity.

That distinction matters.

DSM-5 Criteria: Why Frequency Alone Is Not Enough

DSM-5 conceptualises Gambling Disorder using criteria closely modelled on substance use disorders. Importantly, time spent is not central.

The diagnostic focus is on patterns such as:

-

impaired control,

-

escalating involvement,

-

persistence despite harm,

-

and psychological dependence.

In clinical language, the criteria cluster around four themes:

-

Loss of control

– repeated unsuccessful efforts to cut down

– gambling more than intended -

Psychological dependence

– preoccupation

– irritability or restlessness when trying to stop -

Tolerance and escalation

– needing increasing amounts of the behaviour for the same effect -

Functional harm

– damage to relationships, work, finances

– reliance on others to relieve consequences

What is striking is what DSM-5 does not include:

-

no screen-time thresholds

-

no moral judgement

-

no assumption that pleasure equals pathology

This is a critical lesson for how we think about other repetitive behaviours.

Translating DSM-5 Thinking to Other Behaviours—Carefully

In practice, patients present with behaviours that look addictive but do not meet DSM-5 thresholds.

This is where over-pathologising creeps in.

A person may:

-

game daily,

-

scroll excessively,

-

shop impulsively,

-

or binge-watch nightly,

yet still retain choice, flexibility, and role functioning.

DSM-5 reminds us that addiction is not about liking something too much.

It is about losing psychological freedom in relation to it.

The moment we apply addiction language without impairment, persistence, and loss of control, we convert coping into illness.

The True Pivot Point: Loss of Psychological Freedom

Across substance and behavioural addictions, the most clinically meaningful shift is this:

From “I choose this”

to

“This chooses for me.”

Patients often articulate it clearly:

“I don’t even enjoy it anymore, but I still do it.”

This maps closely to DSM-5’s emphasis on:

-

compulsive repetition,

-

diminished reward,

-

and continued behaviour despite consequences.

Pleasure fades. Rigidity remains.

Why DSM-5 Avoids Moral Models—and Why We Should Too

DSM-5 deliberately avoids framing addiction as:

-

weak willpower,

-

moral failure,

-

or lack of discipline.

Instead, it frames addiction as a maladaptive learning loop involving reward, stress regulation, and impaired control.

This is crucial when working with behaviours embedded in modern life—phones, internet, work, money—where abstinence is neither realistic nor therapeutic.

You cannot abstain from:

-

technology,

-

consumption,

-

stimulation,

-

or reward-seeking itself.

The clinical goal is flexible regulation, not elimination.

A Dimensional Model That Respects DSM-5 Without Overreach

One way to stay aligned with DSM-5 and avoid overdiagnosis is to think dimensionally:

From:

-

enjoyment → coping → avoidance → compulsion

-

optional → preferred → dominant → indispensable

DSM-5 diagnoses sit at the far end of this spectrum, not the beginning.

Most people who worry about behavioural addiction are somewhere in the middle—and benefit more from insight and skills than from labels.

What Treatment Really Targets (DSM-5 Implicitly Agrees)

DSM-5 criteria consistently point toward the same therapeutic targets:

-

impaired self-regulation,

-

emotion-driven behaviour,

-

narrowing of coping strategies.

Effective treatment therefore focuses on:

-

expanding emotional tolerance,

-

restoring alternative rewards,

-

strengthening reflective choice,

-

and rebuilding identity beyond the behaviour.

The behaviour itself is rarely the true problem.

It is the over-reliance on that behaviour.

Final Clinical Reflection

DSM-5 offers an important cautionary principle:

Not everything repetitive is addictive, and not everything distressing is a disorder.

Behavioural addiction, when it truly exists, reflects a loss of freedom—not a failure of character.

Our responsibility as clinicians is to diagnose precisely, intervene proportionately, and resist the temptation to medicalise ordinary human attempts to cope with a demanding world.

That balance is not just diagnostic accuracy.

It is ethical psychiatry.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani), is a Consultant Psychiatrist and Neurofeedback Specialist at Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery, Chennai. His clinical work focuses on behavioural addictions, ADHD, OCD-spectrum disorders, and neuroscience-informed assessment, with a strong emphasis on precise diagnosis and avoiding unnecessary pathologisation of normal behaviour.

📍 Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉️ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808