When Understanding Arrives Late: Autism, Adulthood, and the Relief of Context

Autism is still widely imagined as something discovered early—noticed by teachers, flagged by parents, assessed in childhood clinics. The unspoken assumption is that if it wasn’t picked up then, it must not be there.

Reality is messier.

For many autistic people, understanding arrives late. Not because autism was subtle, but because the world lacked the language, curiosity, or willingness to see it—especially in high-functioning, verbal, masked, or socially adaptive individuals.

A growing number of public figures have spoken about receiving an autism diagnosis in adulthood. Their stories share a common thread: diagnosis did not change who they were. It changed how their lives finally made sense.

The Diagnosis That Explains, Not Redefines

Wentworth Miller has described his adult autism diagnosis as the culmination of a long process—reflection, self-identification, and listening rather than a sudden revelation. Looking back, experiences once interpreted as flaws or failures began to reorganise themselves into a coherent pattern.

Nothing new was discovered. What arrived was context.

This is a critical point often missed in public conversations. Adult diagnosis is not about becoming autistic. It is about understanding how one has always been navigating the world.

Looking Back With New Eyes

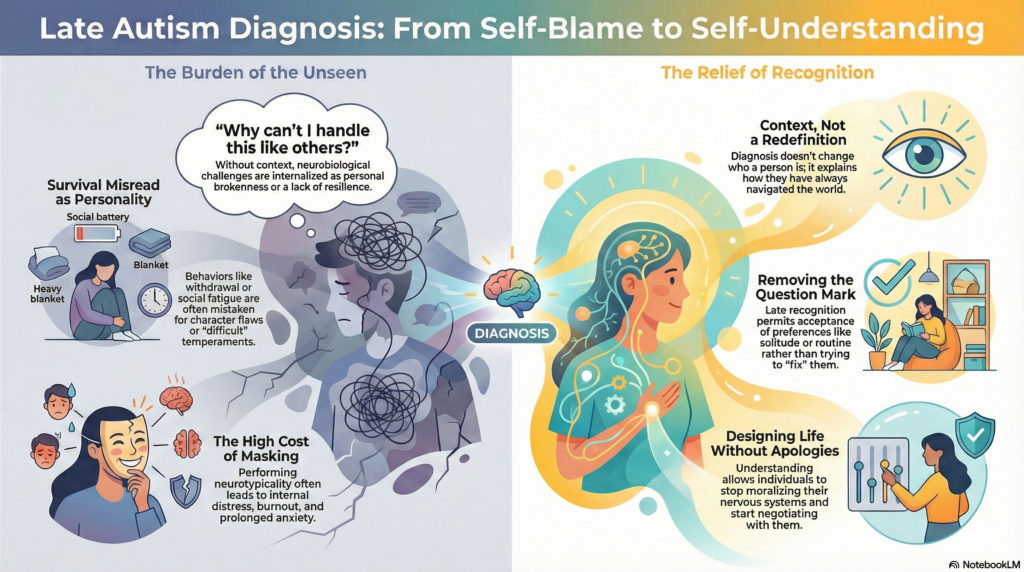

For late-diagnosed adults, the diagnosis works retroactively. Social fatigue, sensory overwhelm, rigid routines, emotional shutdowns, intense focus—what once appeared as isolated quirks or moral shortcomings begin to form a neurodevelopmental narrative.

Moments of “Why can’t I handle this like others?” quietly transform into “Of course this was hard.”

That shift—from self-blame to self-understanding—is often the most therapeutic outcome.

“I Don’t Go to Parties—and That’s Fine”

Anthony Hopkins, diagnosed in his seventies, spoke about autism with characteristic understatement. He noted his preference for solitude, limited social engagement, and deep immersion in work—not as problems to be fixed, but as realities to be accepted.

His diagnosis didn’t add a label. It removed a question mark.

Late diagnosis often does this. It doesn’t demand change. It permits acceptance.

Masking, Burnout, and Late Recognition

Comedian Hannah Gadsby has spoken powerfully about the cost of masking—performing neurotypicality at the expense of mental health. For years, distress was internalised as personal brokenness rather than neurobiological mismatch.

Her diagnosis reframed that suffering.

The problem was not a lack of resilience. It was prolonged adaptation to an environment not designed for her nervous system.

This pattern is particularly common in women and gender-diverse individuals, where social compliance, empathy, and learned scripts often delay recognition until adulthood, frequently after years of anxiety or depressive symptoms.

When Survival Is Misread as Personality

Actor Daryl Hannah has described being labeled “difficult,” “shy,” or “aloof” early in her career. Sensory sensitivity and social overwhelm were misinterpreted as attitude or temperament.

This is a familiar story in adult autism. Behaviours that are adaptive—withdrawal, control, predictability—are mistaken for personality traits, rather than understood as coping strategies.

Late diagnosis often reveals that what looked like character was, in fact, survival.

“The World Needs All Kinds of Minds”

Long before autism entered mainstream conversation, Temple Grandin reframed autism as a difference in thinking rather than a defect. Her words—“The world needs all kinds of minds”—are often quoted, but take on deeper meaning in the context of late diagnosis.

For adults diagnosed later, the message is not just about ability. It is about endurance. About having functioned, contributed, and persisted for decades without a map.

Why Adult Diagnosis Remains So Difficult

Despite rising awareness, diagnostic systems remain largely child-centric. Adults encounter long waiting periods, fragmented pathways, informal assessments, or outright dismissal—often told they are “coping too well” to qualify.

This ignores a central clinical truth: coping is not the same as thriving. Masking has a cost, and that cost often shows up as burnout, anxiety, depression, or relational strain.

Late diagnosis exposes a structural blind spot. Autism does not end at childhood, and insight does not negate need.

What Adult Diagnosis Actually Gives

An adult autism diagnosis is not about labels. It gives language. It allows people to stop moralising their nervous systems and start negotiating with them. It offers permission to design life with fewer apologies and more precision.

In clinical practice, the most meaningful moment is rarely the diagnostic conclusion itself. It is the quiet relief that follows: “So that’s why.”

Not an ending. A reorientation.

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi)

Senior Consultant Psychiatrist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808

Understanding does not always arrive early. Sometimes it arrives late—and still manages to change everything that came before.