Is Quetiapine Safe for Sleep in the Elderly?

Why evidence increasingly says no

Why evidence increasingly says no

Quetiapine has quietly become one of the most commonly used “sleep medicines” in older adults. Many families encounter it when an elderly parent struggles with insomnia, night-time agitation, or confusion.

It is often described reassuringly as a “low dose, just for sleep.”

But when we look at the scientific evidence carefully, a clear message emerges:

Quetiapine should not be used routinely for sleep in elderly patients.

This is not fear-mongering.

It is data.

First, an uncomfortable truth: quetiapine is not a sleeping pill

Quetiapine is an antipsychotic medication.

It was never designed or approved to treat insomnia.

The drowsiness it causes comes from:

-

Strong antihistamine effects

-

Blood pressure–lowering (alpha-1 blockade)

Sedation is a side effect, not a therapeutic goal. And in older adults, side effects often matter more than benefits.

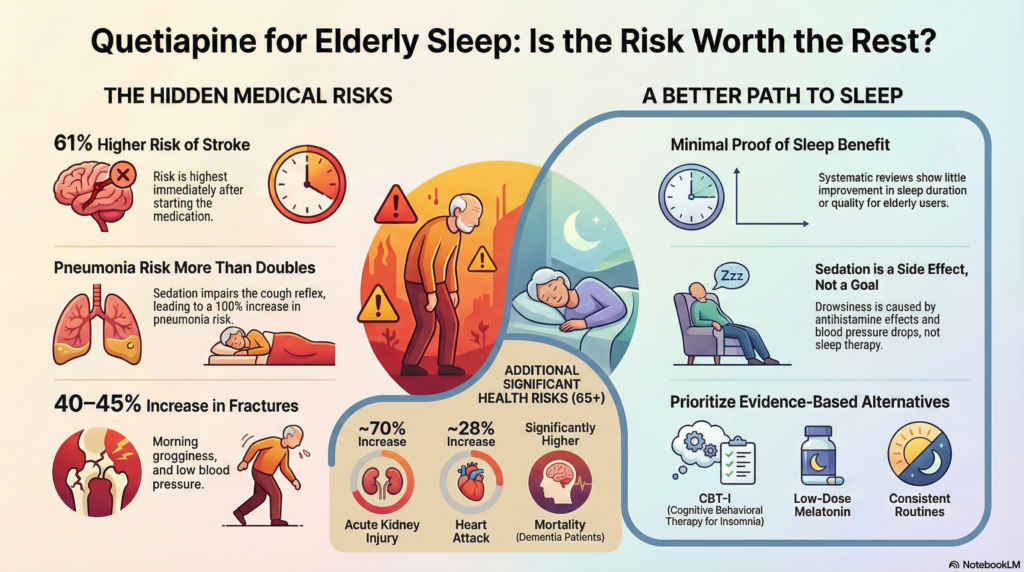

What do large studies show about risks in the elderly?

Multiple large population studies have examined antipsychotic use—including quetiapine—in adults aged 65 and above. The findings are remarkably consistent.

1. Increased risk of stroke

A large UK study published in BMJ found that older adults prescribed antipsychotics had a:

-

61% higher risk of stroke

compared to similar elderly individuals not taking these medications.

This risk was highest soon after starting treatment, a critical point when quetiapine is newly added for sleep.

2. Pneumonia risk more than doubles

The same analysis found:

-

More than a 100% increase (2-fold risk) of pneumonia

Sedation reduces cough reflex, worsens swallowing coordination, and increases aspiration risk—especially in frail elderly and dementia patients.

Pneumonia in older adults is not a minor complication. It is often life-threatening.

3. Falls and fractures increase significantly

Studies consistently show:

-

~40–45% higher risk of fractures

This happens not because patients fall asleep—but because they wake up groggy, dizzy, and hypotensive, then attempt to walk.

Many serious falls occur:

-

Early morning

-

During night-time bathroom visits

-

Within weeks of starting medication

4. Heart and kidney complications rise

Population data show:

-

~28% increase in heart attack risk

-

~70% increase in acute kidney injury

These effects are particularly concerning in elderly patients who already have hypertension, diabetes, or vascular disease.

5. Increased risk of death in dementia patients

Meta-analyses and long-term observational studies show that elderly patients with dementia who receive antipsychotics have:

-

Significantly higher mortality rates than those not exposed

This risk exists across antipsychotics—including quetiapine—leading to the well-known “black box warning” for antipsychotic use in dementia.

But what about low doses like 12.5 or 25 mg?

This is the most common reassurance—and the most misleading one.

While lower doses reduce some risks, studies show:

-

No dose is completely risk-free

-

Frail elderly brains and bodies react differently

-

Side effects accumulate with time, even at low doses

Low dose does not mean low consequence.

Does quetiapine actually improve sleep meaningfully?

Surprisingly, evidence for benefit is weak.

Systematic reviews conclude:

-

Minimal improvement in sleep duration

-

Little improvement in sleep quality

-

No strong evidence supporting long-term benefit for insomnia

So we are left with a troubling equation:

Modest or uncertain benefit + clearly demonstrated harm

That is not a good trade-off in geriatric care.

Why is quetiapine still being used so widely?

Several reasons—not bad intentions.

-

Elderly insomnia is complex

-

Dementia-related night disturbances are difficult

-

Benzodiazepines and zolpidem have their own risks

-

Non-drug sleep therapies are underused

-

Time pressures in real-world practice are real

But difficulty does not justify unsafe shortcuts.

When should quetiapine not be used for sleep?

Quetiapine should be avoided for insomnia alone in elderly patients with:

-

History of falls

-

Stroke or heart disease

-

Dementia

-

Parkinson’s disease

-

Diabetes or metabolic syndrome

-

Excessive daytime sleepiness

If quetiapine was started years ago “just for sleep” and never reviewed, that itself is a red flag.

What should be done instead?

Safer, evidence-based approaches include:

-

Identifying causes: pain, anxiety, depression, urinary problems

-

Daytime light exposure and activity

-

Consistent sleep routines

-

Low-dose melatonin

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)

-

Treating dementia-related triggers without defaulting to sedation

Good sleep in the elderly is built—not knocked unconscious.

The take-home message

Quetiapine may make an elderly person sleep—but at a cost that is often hidden.

The evidence shows:

-

Higher risk of stroke

-

More pneumonia

-

More fractures

-

Higher mortality in dementia

-

Little proof of real sleep benefit

For these reasons, routine use of quetiapine for sleep in the elderly should be discouraged.

The goal of geriatric psychiatry is not silence or sedation—it is safety, function, and dignity.

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808